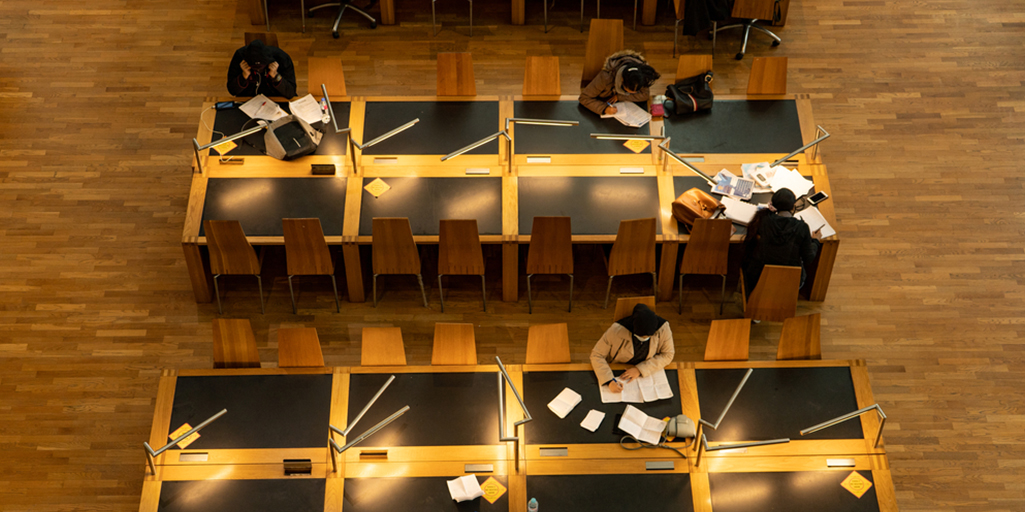

Let’s take a look at a residential, working-class, red-brick neighborhood on the outskirts of Barcelona. An area where there are neither tourists nor labels on social networks. Now let’s think about what can change that peripheral place. As it is in Barcelona, it would be enough to include some of its buildings within a modernist route. Or plan something that ends up in the sea. However, what makes people flock to this kind of street now is neither Gaudí’s architecture nor the Mediterranean breeze: it is a library in honor of Gabriel García Márquez, built entirely out of wood and with elements reminiscent of that Macondo that the Colombian writer imagined.

This example, which is real, takes place in Sant Martí, a district of the Catalan capital with more than 220,000 inhabitants. This building was inaugurated there a few months ago as a meeting point and, beyond the simple tasks of a public service space, it has become a landmark. People from other areas come here to admire the work of the author of One Hundred Years of Solitude, browse through its more than 40,000 titles, and lie down to read in a hammock that simulates that magical universe of the Caribbean.

Something unexpected like this project is capable of changing the appearance of a neighborhood. “It has invigorated it. Activities are scheduled, the masterpieces of Latin American literature are offered and one can feel the Nordic influence adapted to the venue’s reality. It is attracting a huge audience,” explains Jordi Gual, technical director of the Barcelona libraries. Thinking of offering a cultural enclave, they have managed to become a reference point. A “people’s palace,” according to the definition by the American sociologist Eric Klinenberg.

And it is not usually easy: as Jane Jacobs said, not everything responds the same to a specific purpose. “When we deal with cities we deal with life in all its complexity and intensity. And since this is so, there is an aesthetic limitation in what can be done with cities: a city cannot be a work of art,” claimed the activist in her book The Death and Life of Great Cities, first published in 1961.

Cities, indeed, are an organic entity. They are altered, mutated or stagnant due to sometimes unforeseen factors. A complete remodeling can be planned, as happened in Bilbao, and be successful. Or a whole new port can be designed, with stands for sailing championships and a Formula 1 circuit, and end up failing. Planning on paper is not enough for a city to work: there are hidden ingredients, intangible dynamics that spice up or spoil the recipe. The balance between design and the needs of citizens is what makes the perfect soufflé.

At the moment, the adversities that the city is facing are manifold. And they have been a long time in the making. One is the ability to offer residents a comfortable and sustainable space. The terms that we hear the most are “15-minute city” and “superblocks”, which consist of bringing together everything at a manageable distance for people’s main activities: work, school, shopping, and exercise. Two motivations predominate in both: to give pedestrians their space back and to be respectful of the environment.

A trend that has been highlighted for some time and that, with the pandemic, has gained strength: teleworking has established a precedent on how we spend our commuting time, and the spread of Covid-19 has highlighted the danger of closed spaces such as community transport, and the rewards of the familiar: as Ramón Lobo says in his essay The evanescent cities, those meeting places, the places where we ask for “the usual,” make us feel that we belong to a group, an essential condition of being human.

In this way, the political agenda has been conforming to implicit demands. Almost all medium and small cities already had open-air areas where residents could practice sports. Now, to cite two Spanish examples, Madrid and Valencia have restricted traffic in parts of their central areas and have extended bike lanes. In others, this change goes further: the towns of Amorebieta (Vizcaya) and Chirivella (Valencia) have abolished traffic lights, replacing them with squares and pedestrianized streets. In the first city this was carried out in 2000 and, according to data from the town hall, it reduced traffic from 40,000 to 15,000 cars. In the second, accidents have decreased by 70% and the 450 zebra crossings that shine on its streets are already a hallmark.

Portishead, about 200 kilometers from London, saw even more radical changes. There, they not only removed traffic lights, but also removed all the signs. They did it in September 2009, based on Hans Monderman’s “shared space” theory. This Dutch engineer claims that less regulation gives citizens greater responsibility and that they abide by it in a positive way.

The project has been fruitful, according to The City Fix website: the coastal city, with a population of 22,000, has overcome the traffic jam problems that plagued its city center, saving resources and proving that naked streets do not reduce the safety of pedestrians or drivers. It seems that they even increase “common sense and courtesy on the road.”

Traffic lights, signals, isolated lanes and an ultra-fast bus, as proposed for the outskirts of Madrid, are included in this new paradigm. The cherry on top are pedestrians, who are increasingly concerned about carbon dioxide emissions and demand more mobility options: public bicycles, electric scooters and even car hire by the minute. The concept around these new models is that of a smart city.

Rafael Pla, president of the consulting firm Innovall, defines this as the city that “uses new technologies to improve the quality of life of its inhabitants, identifying their needs and ensuring that urban development follows three sustainable directions: the economy, society, and the environment.” Mobility, says the expert to Ontheroad, “is experiencing a rethinking” in terms of “carbon dioxide emissions and how to minimize them.” One of the pillars in this sense is the paradigm shift in transport, pushing for collective transport which does not use fossil fuels.

“According to the political strategies of Europe and organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO), cities are going to evolve to meet the 2030 and 2050 objectives regarding environmental pollution,” he argues. That means “more sustainable buildings with new and recycled materials, more green spaces and integrated nature.” They will also offer better connections and less traffic, more pedestrian streets and houses with more light, open and community spaces. “Digital transformation is a fact,” adds Pla, who has faith in a good use of ethical technologies, “with ethical perspectives.”

But there are still obstacles. In most large cities, the car is king, and people need to travel tens of kilometers a day to get to and from work, even after the dynamics imposed by the pandemic. In the words of Manuel Romana, a civil engineer at the Polytechnic University of Madrid, many citizens “live and work where they can.” In other words, without a structural change (such as teleworking) it is difficult to feel any change.

“An example is what North Americans call the central business district, which here would be something like the historic center. There, cars are becoming less relevant, but most journeys are made between two points with poor public transport options,” concludes Romana. All these initiatives are leading to a new model. The answer lies in everything from roundabouts, bicycle apps and a library on the outskirts.